Software Part 2

Then

It was time to add some Python to the picture. Python is language of choice for the Games Creators Club where we use pygame to make some 2D games (see here for some of the games made in previous years), so it makes perfect sense for it to be the main language for controlling our robot rover.The method for moving a servo for our rover is quite simple given that most of the work is done in servoblaster (seer Software Part 1):

def moveServo(servoid, angle):

f = open("/dev/servoblaster", 'w')

f.write(str(servoid) + "=" + str(angle) + "\n")

f.close()

A simple scp of the python file to the Raspberry Pi and running it has shown that it is quite quick (especially given it is Raspberry Pi 3). But, an scp followed with ssh is something we couldn't easily accommodate on our club as most of members used the school computers that didn't have any of those commands, nor were allowed to be install them. Plus mastering those commands would add more of a bulge to our learning curve. Finally there was the issue how would some controlling device connect/talk to the rover. One of the obvious choices would be bluetooth, but that would require more hardware (bluetooth game pad for instance) and special programs to accommodate. More to add to the learning curve. One of the alternatives is that we could have used sockets and a custom protocol for them, but that would mean learning how to connect to a socket and how to create server socket and accept connections.

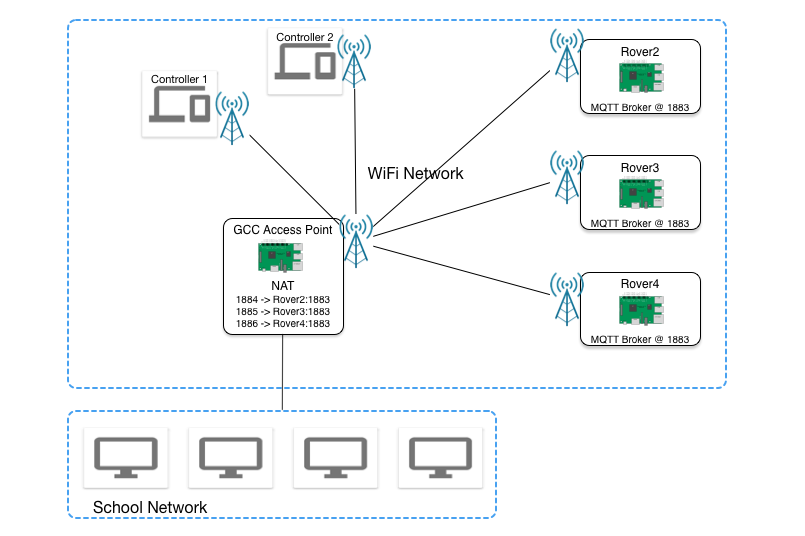

In the mean time another alternative presented itself (or rather was kindly suggested by a fellow roboteer on the Robox 3D printer user forum): a MQTT protocol. It is lightweight, has very simple API and Python client (paho) and is supported by the Raspbian distribution (mosquitto broker's package for instance). Next was to organise network so our rover can be accessed from inside of club's WiFi network and/or school computers:

Pyros

And the last thing was to supply simple way of making programs on school network and then 'executing' them on the rover. That is how our Python Rover Operating System (pyros for short). In essence it is a python process executed as a service (from /etc/init.d/pyros script) which listens to specific topic over MQTT and accepts python code which, then, when requested it executes in a separate python process. Simple! All the output (sysout) from such newly created process is broadcasted back to another topic so we can see the 'debug' output. Some of such 'programs' can be made into 'services' so they are automatically started when the Raspberry Pi boots. A simple python library on the developers machines is responsible to send an 'agent' (or service) to the selected rover and helps displaying the feedback (sysout received is just printed out). For instance our straight line code on the developer's machine looks like this (this is a sketch with unnecessary stuff taken out:...

screen = pygame.display.set_mode((600, 600))

...

def connected():

pyros.agent.init(pyros.client, "straightLine-agent.py")

print("Sent agent")

def onKeyDown(key):

if key == pygame.K_UP:

pyros.publish("straight", "forward")

elif key == pygame.K_DOWN or key == pygame.K_SPACE:

pyros.publish("straight", "stop")

...

pyros.publish("straight", "calibrate")

pyros.init("straight-line-#", unique=True, onConnected=connected...)

while True:

...

pyros.pygamehelper.processKeys(onKeyDown, onKeyUp)

pyros.loop(0.03)

screen.fill((0, 0, 0))

...

pygame.display.flip()

frameclock.tick(30)</pre>

Similarly, example 'echo' service looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/python3

import pyroslib

def handleEcho(topic, payload, groups):

pyroslib.publish("echo/out", "default: " + payload)

if name == "main":

try:

print("Starting echo service...")

pyroslib.subscribe("echo/in", handleEcho)

pyroslib.init("echo-service")

print("Started echo service.")

pyroslib.forever(0.5)

except Exception as ex:

print("ERROR: " + str(ex) + "\n" + ''.join(traceback.format_tb(ex.__traceback__)))</pre>

That way we can have python programs that are permanently sent to the rover and started at the boot time performing some 'service'; 'agents' that are sent at the start of the client program which will execute some work 'close' to the hardware (gyro, accelerometer, distance sensor, camera, motors, ...) and client program which can talk to any service and/or agent where latency is not that much of an issue or it is only way (driving controller which reads locally attached joystick/game pad and controls/moves the rover).

First service that was written for pyros was 'wheels' service. That service was listening on 'wheel/<name>/deg' and 'wheel/<name>/speed' where <name> was one of 'fl', 'fr', 'bl' and 'br' (for front left, front right, etc). 'Deg' topic was expecting message consisting of angle for that wheel in degrees - a value between '-90' and '90', while 'speed' topic was expecting message containing speed in RPM - a value between '-300' and '300'.

Now

Pyros evolved since then and it now has three distinct parts:

- the pyros process itself - a python program sent to Raspberry Pi using scp (once) and started by service;

- a set of command line/shell scripts/commands to control pyros (upload program/service; start/stop/restart any of them; display list of 'known'/running programs/services; remove existing, etc)

- set of server side and client side libraries to enable easy integration with pyros (subscribing to MQTT topics and receiving messages on them; publishing to topics; sending agents and displaying agents' output; maintaining program loops dividing time between 'listening' to socket messages so MQTT client can work and 'sleeping' so Raspberry Pi CPU is not 100% all the time; etc...)

Recently we've updated most of our code to use such libraries so our programs can be more readable and has less 'fluff' - less boilerplate code needed for MQTT to work. The above examples show that really nicely.

Currently our rovers have the following 'core' services deployed on them:

- storage - service that provides other services with persistence. It listens to 'storage/read' and 'storage/write' topics, persists changes sent to them and reads requested values. It is coupled with storagelib, a library to be used by other services for ease of use of storage service.

- wheels - service to command steering servos and motor controllers. It uses storage service to obtain calibration data for each wheel.

- lights - service to control LEDs on the rover

- shutdown - service which reads state of one GPIO which is connected to a switch and when such switch is moved from 'off' to 'on' state executes 'sudo shutdown -h now' command. Before such command is executed LEDs are flashed allowing grace period for shutdown to be aborted (by moving switch back to 'off' position)

- gyrosensor - l3g4200d gyroscope service

- accelsensor- adxl345 accelerometer service

- mpu9250 - service which provides same functionality as above two - on same topics of MQTT for compatibility.

- sonarsensor - hc-sr04 sensor + servo service for obtaining distance

- camera - service to fetch raw and processed images form the built in camera

Since we've mentioned the wheels service there was a problem recently to be solved. Motor controllers are designed to have 'dead' zone somewhere in the middle. That prompted us to 'find' that zone and make wheels service use it. That way speed got four calibration points instead of three. Previously we had '-300', '0' and '300' points to be calibrated - points where each wheel would spin as fast as possible back, would be stationary and would spin as fast as possible forward. Because of dead zone we introduced '-0' point as well. At '-0' wheel would be just one step before spinning backward and at '0' just one point before spinning forward. That way speeds of '-1' and '1' result with wheels moving(*) back/forward.

(*) free spinning wheels at those power levels do not mean rover moving, too.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus