Losing IMU Data

Losing IMU Data

Investigation and Solution

Introduction

This article discusses some of the problems I encountered whilst using a Raspberry Pi to read data from a complex sensor at approx 200Hz.

If you're short of time, just skip to the conclusions at the end of the article.

System Overview

The system contains an IMU (an LSM9DS1), a sensor which provides acceleration, angular rate and magnetic field measurements. The IMU has a "Data Ready" output pin. It sets the pin to 1 when new data is available and clears it when the data is read. There's also an API call which provides the same information. This "Data Ready" output is connected to a GPIO input on the Raspberry Pi.

The positioning system spawns a process to gather data samples. I call this a "Data Pump".

The IMU produces samples at 230.8 Hz. i.e. once every 4.3 milliseconds.

The Test

One of the first tests of my positioning system was to move the Pi backwards and forwards a couple of times. Each movement was about 1 metre and it accelerated at about 0.5g.

I recorded the raw IMU data as well as the output of the positioning system. I then spent the next month analysing the results and fixing things. I'd no idea that such a simple test could highlight so many issues! Most of these concerned the Madgwick algorithm I was using to determine the Pis attitude.

After I'd solved these problems I began to suspect that the data from the IMU was wrong in some way. It looked like the positive and negative accelerations didn't add up to zero even though the test started and ended with zero velocity.

Sample Data

Here's a few lines of the raw IMU data showing just the acceleration and gryo outputs while the Pi is stationary. Each row shows the sensor output at a point in time. The "dt" column shows the time between samples in milliseconds.

The IMU outputs are 16 bit signed integers. You can see this clearly in the acclerations for the z axis (Az). The full range of the accelerometer is 2g so 16384 represents 1g.

| Sample | Ax | Ay | Az | Gx | Gy | Gz | dt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -227 | -149 | 16318 | -6 | -65 | -127 | 2.30 |

| 2 | -228 | -150 | 16359 | -13 | -70 | -128 | 6.94 |

| 3 | -228 | -150 | 16359 | -13 | -70 | -128 | 2.33 |

| 4 | -244 | -147 | 16356 | -3 | -50 | -125 | 2.51 |

| 5 | -230 | -139 | 16355 | -14 | -55 | -121 | 6.94 |

| 6 | -230 | -139 | 16355 | -8 | -70 | -119 | 2.34 |

| 7 | -242 | -154 | 16340 | -2 | -51 | -114 | 6.92 |

| 8 | -242 | -154 | 16340 | -2 | -51 | -114 | 2.30 |

If you look at lines 2 and 3 you can see that the data is identical. The same thing happens with lines 7 and 8. Given that these measurements are noisy it's vastly improbable that this happens at all, let alone twice in 8 samples. Those 8 lines are typical of the whole data set. In other words, at least 1/4 of my data points were invalid.

Analysis

At the time I gathered this data, the Data Pump was simply reading the IMU output at regular intervals. This was good enough for me to get going and allowed me to use someone else's driver.

When I wrote it, the polling interval was very predictable. If you look at the dt column you can clearly see it's not very predictable in this case. In fact, the interval between samples seems to be flip-flopping between a long and a short interval. In each case where there are duplicate rows, the interval between first and second row is a short interval. This happens because the IMU hasn't managed to gather a new sample before the Data Pump reads the data again. In this case it simply hands over the previous value.

If you compare lines 5 and 6 you can see a slightly different problem. The acceleration values are identical but the gyro values are different. With this IMU the accelerometer and gyro values are always captured at the same time. So what happened? The answer is that the IMU produced a new sample just after the Data Pump read the accelerations and just before it read the gyro. It got half of one sample and half of another.

There's actually an even more insidious variation of this problem. The IMU doesn't set the high and low bytes of each value at the same time. It's possible to read a value with the high byte from one sample and the low byte from a different one. This tends to show up as a value that approximate 250 points higher or lower than expected.

To summarise, the underlying problem is that the Data Pump was reading data from the IMU without knowing whether a new sample was ready or not.

Using the Data Ready Pin

The obvious solution to these problems was to change the Data Pump to wait for the "Data Ready" signal and then read the data. As long as the Data Pump notices that data is ready and reads it within one cycle it will always get a new and self-consistent sample.

I connected the IMU's Data Ready pin to a GPIO (general purpose input/output) pin and used this GPIO code to wait for the pin to rise from 0 to 1.

return GPIO.input(self.gpio_pin) or GPIO.wait_for_edge(self.gpio_pin, GPIO.RISING, timeout=timeout)

This uses GPIO.input to see if the pin is already set. If not, it waits for the pin to go high.

I gave it whirl and checked the output from the IMU. The good news was that all the samples looked different. There were no more obvious duplicates.

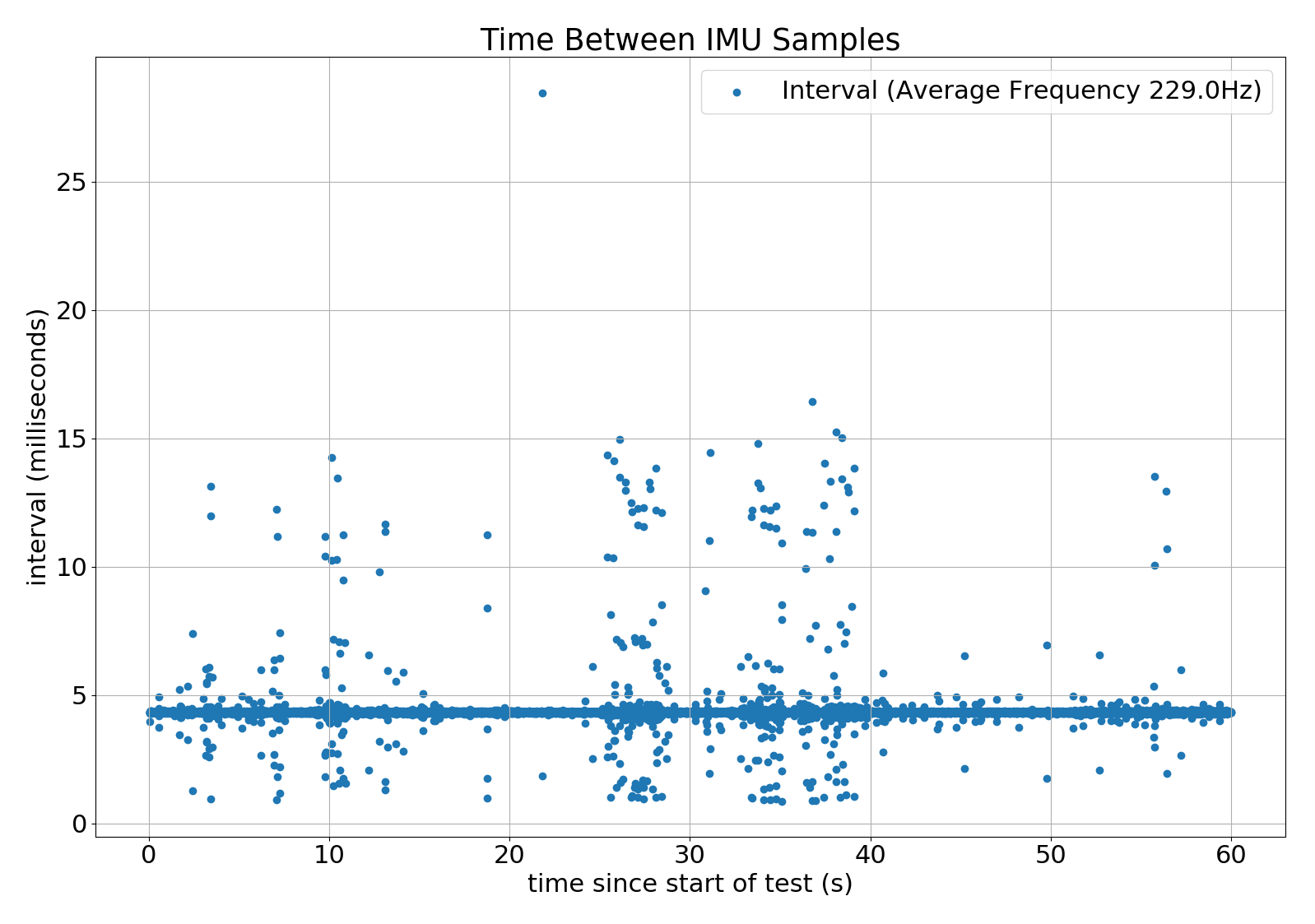

One big surprise was the sample rate. According to the data sheet it should have 238 Hz. It actually came out at 229.9 Hz.

The time between samples looked better but not perfect. As you can see from this graph the time between samples was usually 4.3 milliseconds but was sometimes so high that the Data Pump must have lost samples.

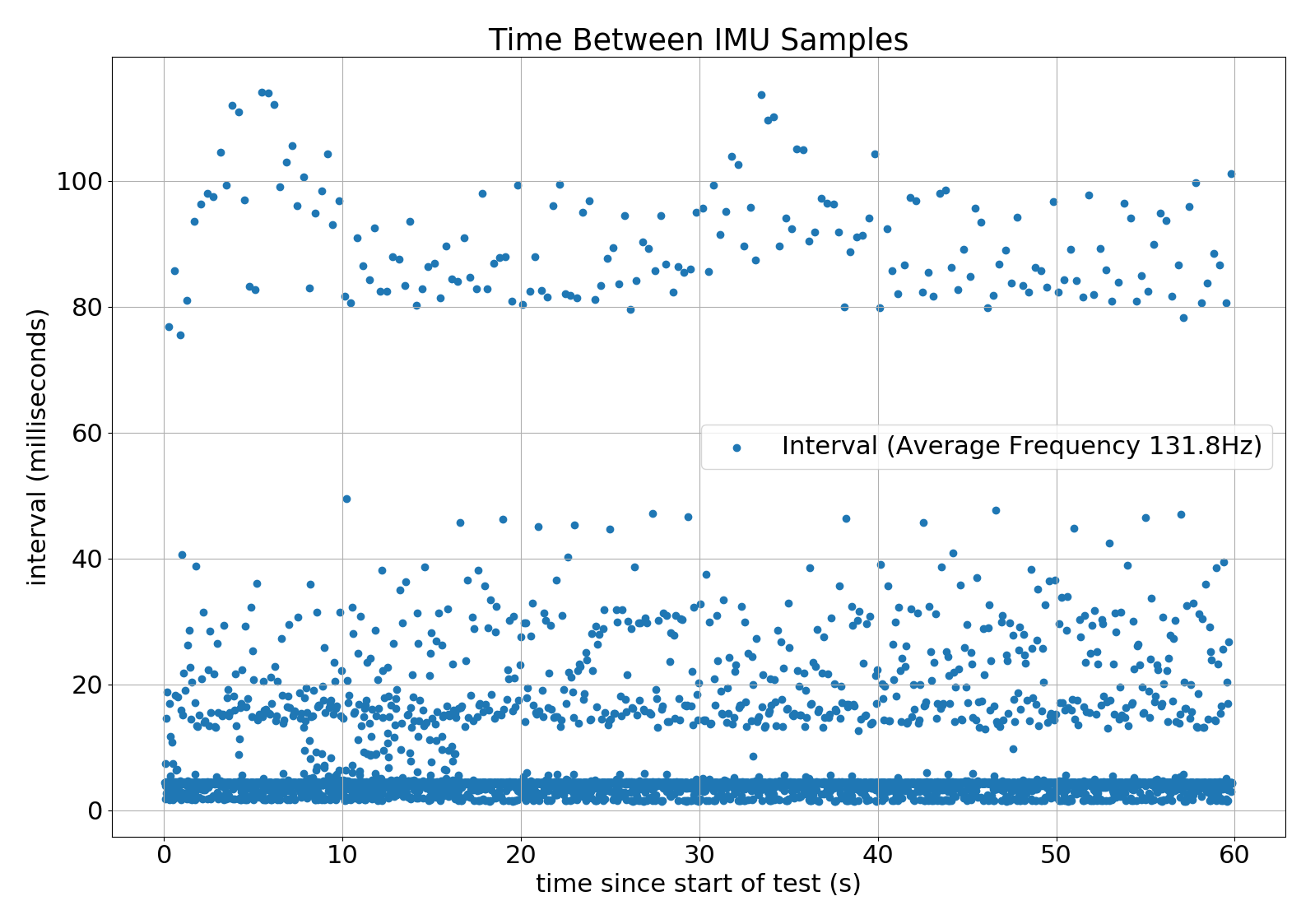

For reasons I didn't understand at the time, the CPU load on the positioning system and Data Pump would often double. (I later discovered that this was caused by the Pi throttling the CPU when it detected a low voltage condition on the power input.) I also wanted to be able to record data and run diagnostics while the system was running without affecting it so I decided to stress the system by turning on all my diagnostics and logging. The results were not pretty!

If you check the scale you can see that in some cases it took more than 100 milliseconds to get a sample. In other words, the Data Pump must have lost about 20 samples. The scale of data loss is reflected in the average sample frequency which has dropped to 132 Hz. This is clearly not good enough.

Some Experiments

As you can imagine, I was a bit worried about these results. Clearly there was something wrong; possibly several somethings. I tried lots of experiments and established the following: the results were identical whether the Data Pump read the GPIO pin or called the API to get the Data Ready status there was no significant delay between detecting Data Ready and reading the data * if I increased the timeout while waiting for new data to several times the expected interval it would still time out occasionally

All this suggested that either the IMU wasn't setting the Data Ready status at regular intervals or GPIO.wait_for_edge wasn't detecting edges reliably.

At one point, I changed the call to GPIO.wait_for_edge to a tight loop that called the Data Ready API. That worked much better but meant that the Data Pump took 100% CPU. 100% CPU use isn't acceptable so I changed the implementation to sleep for a while between loops. All the problems came back. Gah!

After a bit of head scratching I came to the following conclusion: GPIO.wait_for_edge doesn't detect events reliably. My suspicion is that it usually works as long as the calling process is scheduled and doesn't work if the Linux process scheduler de-schedules it to let something else run for a while.

Final Code

In the end I made 2 changes to the code. First of all, I dropped GPIO.wait_for_edge and reverted to polling GPIO.input instead.

def wait_for(self, timeout: int) -> bool: """ Returns true if when the pin transitions from low to high. Assumes some other process will reset the pin to low. :param timeout: time to wait for the interrupt in milliseconds :return: True if the interrupt happened. False if it timed out. """ ready = False sleep_time = (timeout / 1000.0) / 30 stop_time = time.monotonic_ns() + (timeout * 1000_000.0) while not ready and time.monotonic_ns() < stop_time: ready = GPIO.input(self.gpio_pin) time.sleep(sleep_time) return ready

I call this with timeout set to approx 1.5 times the expected delay. The factor of 30 means that the sleep time is approximate 1/20th of the total time to wait. This gives me an acceptable balance between CPU usage and timeliness.

This change isn't enough on its own as time.sleep() invites the Linux process scheduler to deschedule the Data Pump. This leads to periods of around 10 milliseconds when the Data Pump isn't running. The final fix is to make the Data Pump a high priority process. This tells the Linux process scheduler to return control to the Data Pump in preference to other processes.

priority = os.sched_get_priority_max(os.SCHED_FIFO) param = os.sched_param(priority) os.sched_setscheduler(0, os.SCHED_FIFO, param)

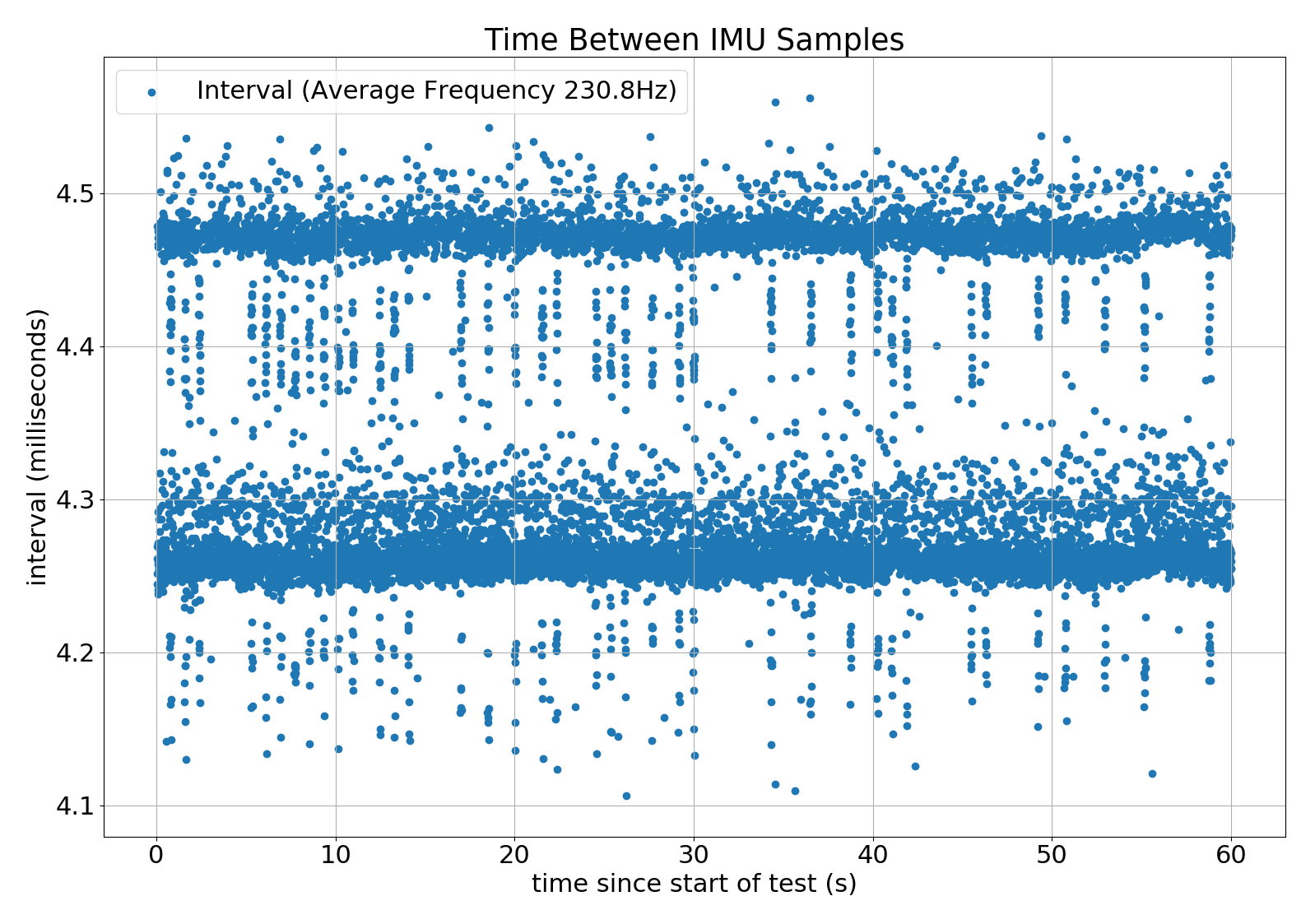

As you can see from these results, I now get samples reliably and in a timely manner.

The average of these intervals is about 4.3 milliseconds as expected. The gap between the two dense lines across the graph is the equal to sleep time. i.e. it's the time between two polls. Polling more frequently would bring these lines together at the expense of more CPU load. I found that reducing the polling interval by a factor of 10 doubled the CPU time and reduced by the spread by a factor of 10.

The CPU load on the Data Pump is around 27% which is acceptable.

Conclusions

- Many sensors provide some form of "Data Ready" indicator. You may get invalid or subtly incorrect data unless your system waits for Data Ready before reading the sensor.

- GPIO.wait_for_edge() does not detect edges reliably. In some circumstances it misses some events completely.

- A normal priority process cannot be relied on to events at frequencies over about 5 Hz.

- The Raspberry Pi 3 B+ throttles the CPU when it detects low voltage from the power supply. This makes the CPU load appear to double.

- Even though Raspian is not a real time operating system it can be made to sample data reliably at approx 200 Hz on a Raspberry B 3+. (At least under certain circumstances.)

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus